A Review by Tsutomu Saito

Originally published in Japanese on note.com

I traveled to Venice, Italy from the end of April to early May. My main purpose was to see Pierre Huyghe’s Liminal, but since the Venice Biennale was taking place, I planned to visit after the April 20th opening. I had read several reports about previous Venice Biennales during my graduate research, and I felt I needed to experience it firsthand. This seemed like the perfect opportunity. I plan to write a separate review of Pierre Huyghe’s exhibition.

Rather than providing explanations of works or artists, I want to write down what I saw and what I thought about it as notes.

My Venice Biennale experience.

Planning and Arrival

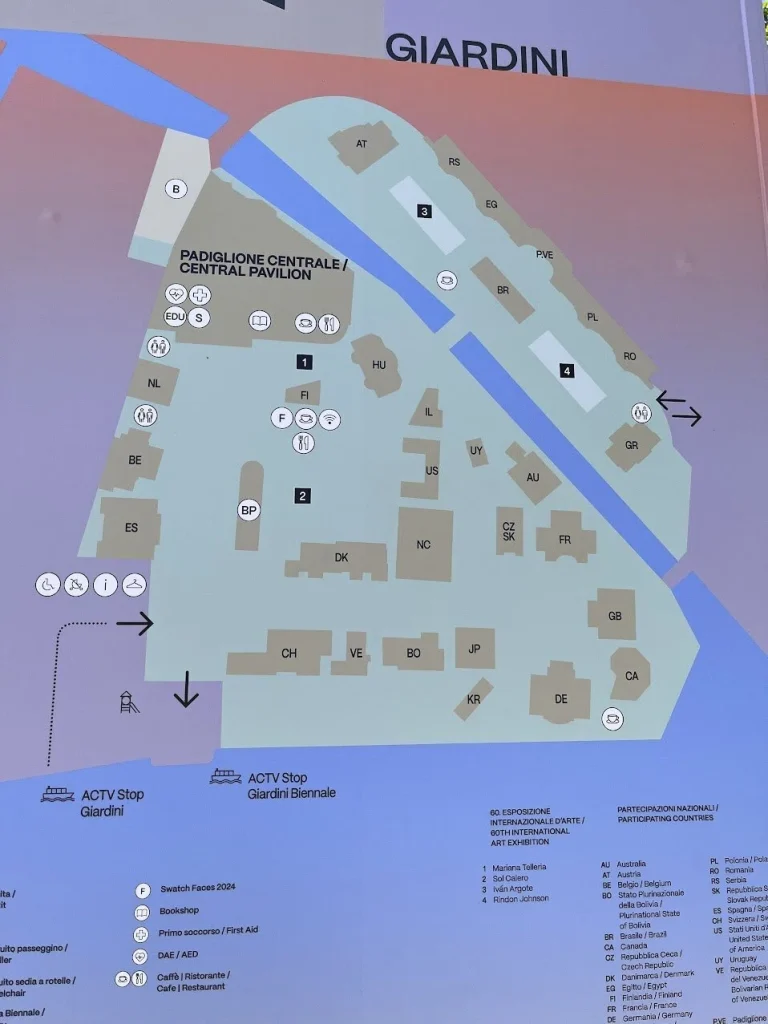

The Venice Biennale is held every two years in Venice and is the world’s oldest art festival, attracting global attention. The main venues are ARSENALE and GIARDINI, and during the exhibition period, various national pavilions and related exhibitions are also held throughout Venice’s main island and surrounding areas (islands). Despite researching extensively, I couldn’t quite grasp the full scope, and while there is a catalogue, it doesn’t seem to include all the works.

For my three-day stay, I purchased a 3-day ticket online. A unique QR code entrance ticket was sent via email, which I printed in Japan. I think you can display and scan it from a smartphone screen, but having a paper copy felt more secure.

Initially, I thought I would need to use water buses, but you can actually walk to both venues from Santa Lucia Station.

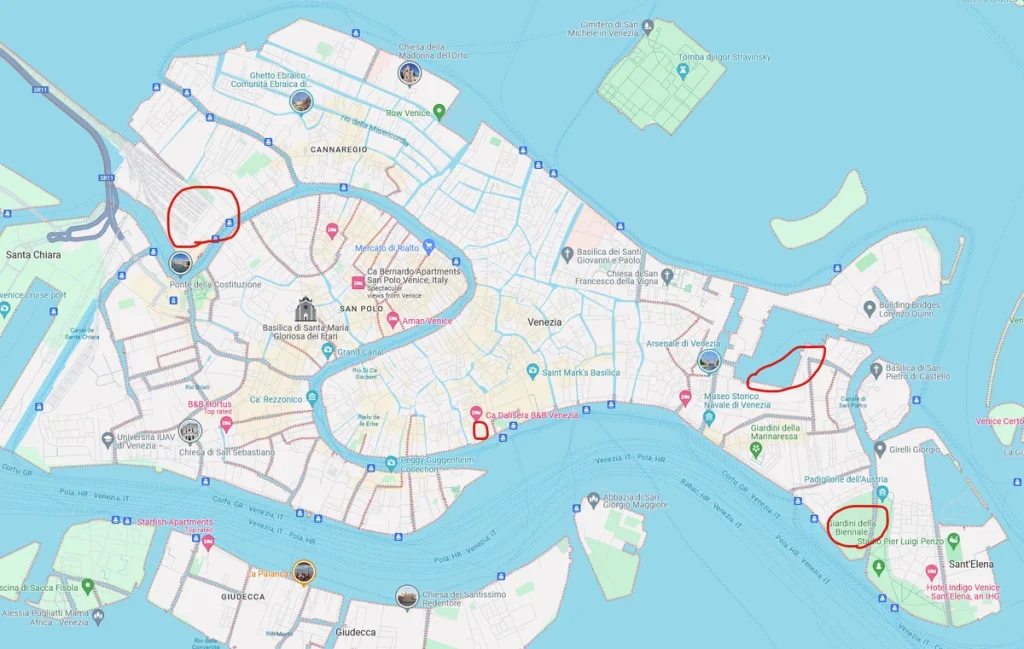

Looking at the map, the red circle on the left shows Venice Santa Lucia Station. From there, you can take a water bus to easily reach the venues. Walking involves about an hour on stone-paved roads, but all areas are connected by bridges, so it’s entirely walkable. During my three-day stay, I traveled everywhere on foot.

The green area with the red circle on the right is GIARDINI, with ARSENALE above it, and the small red circle in the center is the headquarters. There are related exhibitions in various other locations as well.

There are several guide apps available, but they include unnecessary information (like food guides), making the volume of information confusing. This time, I set the bottom line goal of seeing both main venues.

First Day: Discovering the Unexpected

I arrived at the venue with plenty of time to spare. Tuesday morning, with strong sunlight but pleasant, crisp weather. Long queues had formed 30 minutes before opening. Since Monday is closed, Tuesday might be particularly crowded. Groups of local art students were also waiting in line.It took about 10 minutes from opening to actually enter the venue. Ticket purchases also seem to start from opening time, so buying in advance is recommended.

The queue for entry was about 100 meters long and continued to grow afterward.

First, I planned to see the Japan Pavilion, Yuko Mohri’s exhibition. The venue is spacious, feeling roomy compared to the crowds waiting outside.

There was an installation in the pilotis area as well, with light bulbs flickering on and off.

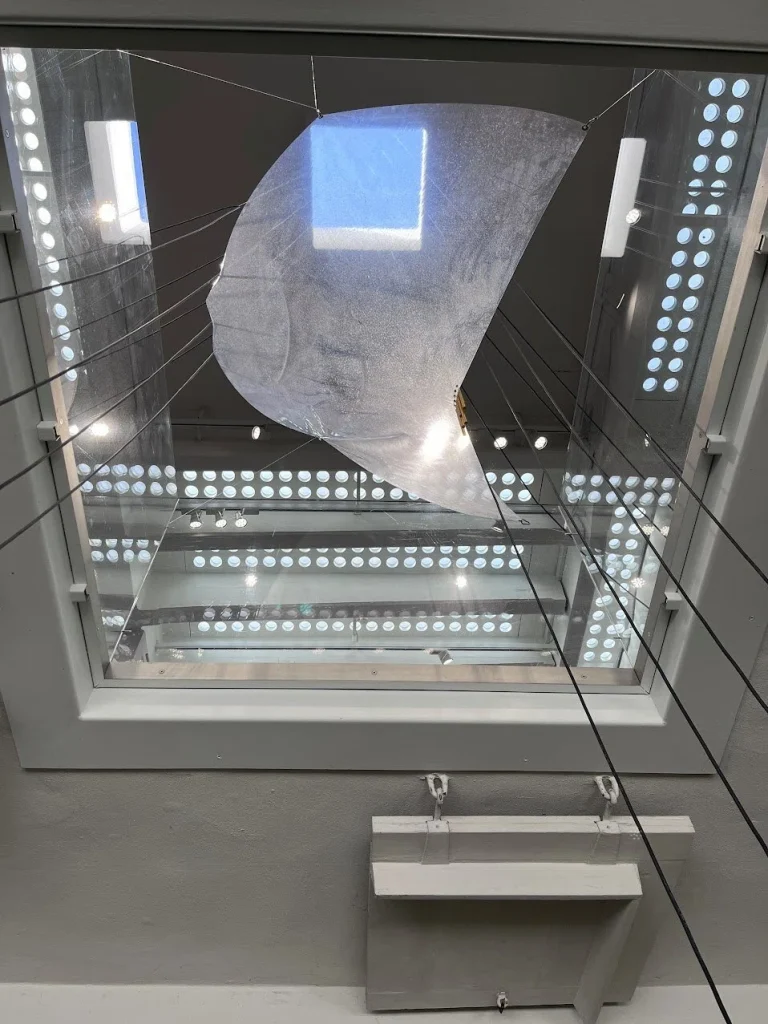

Looking up at the ceiling, you can see skylights designed to invite rain. The Japan Pavilion’s architecture appears to be simple concrete blocks, but I discovered it has this kind of open-air mechanism. It seems like a device for coexisting with nature.

Wide-ranging sounds resonate throughout the venue.

The chest-high shelves in the back must be speakers. The sliding doors appeared to be made of speaker-like fabric. I realized later that what I thought were antique patterns on the doors were actually drawings.

Fruits left to decay, with electrodes inserted, causing light bulbs to flicker as if transmitting their pulse. A faint smell of decomposition permeates the venue.

The water circulation installation produces operational sounds from its machinery, along with sounds from speakers. It didn’t sound like music, but it didn’t seem discordant either.

I wonder how it would look when it rains. The fruits will continue to decay, and the sounds will probably change accordingly. It was an exhibition that foregrounded circulation and time. On the third day, there was heavy rain, and I really wanted to see how it looked with rain falling, but by 11 AM opening time, the rain had completely stopped.

Exploring the National Pavilions

After seeing the Japan Pavilion, I surveyed the full scope of Giardini.

Giardini houses national pavilions, a venue that showcases both architecture and art, where you can see each country’s ambitious exhibitions.

I attended a report session about the 2019 Venice Biennale at the Roppongi venue. I remember discussions about how heads of state, or at least top-level ministry officials, come for the opening from each country, but Japan doesn’t place as much importance on this.

The German Pavilion was popular. There were queues for entry and it was somewhat crowded. Inside, smoke was being produced, creating a hazy, fog-like atmosphere where light traces were visible. It seemed dusty, but it was from smoke machines, creating an illusion of breathlessness.

Just inside the entrance, there was a spaceship model in a small room. The smoke seemed to emphasize how the light appeared.

The central room had a curved screen installed, showing alternating footage of the spaceship flying and ritual-like dancing in a forest. The central structure featured a three-story house-like installation.

The spaceship had a structure of several connected spheres, suggesting it wasn’t launched from the gravity-bound earth. It seemed impossible to construct with current technology, evoking the future. The ritualistic forest dancing might function as records for understanding the past while wandering in this spaceship in a future world—that’s what I thought. Because inside the central house, you could see dust-covered traces of life, suggesting a world already devoid of people. On the building’s rooftop within the pavilion, footage of a man digging holes was being shown.

What the German Pavilion presented seemed to be a loosely connected group of works. Archive, future, and planetary boundaries. They appeared simply juxtaposed, but what was their relationship?

The third room had spaceship posters that visitors could freely take. Was this about the real world or a recreation of a future world? The nested structure often made me consider the relationship between myself and the world.

The French Pavilion’s exhibition showed relationships between resin, thread, and objects, with video works presented on the walls and sounds that couldn’t quite be called music flowing. This gave me hints for an exhibition I’m currently planning at the gallery.

Playing sounds in exhibitions. Not necessarily music. I heard some kind of sound in almost every national pavilion. Whether from videos, environmental sounds, or something else, auditory stimulation from sound seemed to be treated as importantly as visual stimulation from viewing the works.

Central Pavilion and the Theme

The Central Pavilion displays a massive number of paintings and sculptural works.

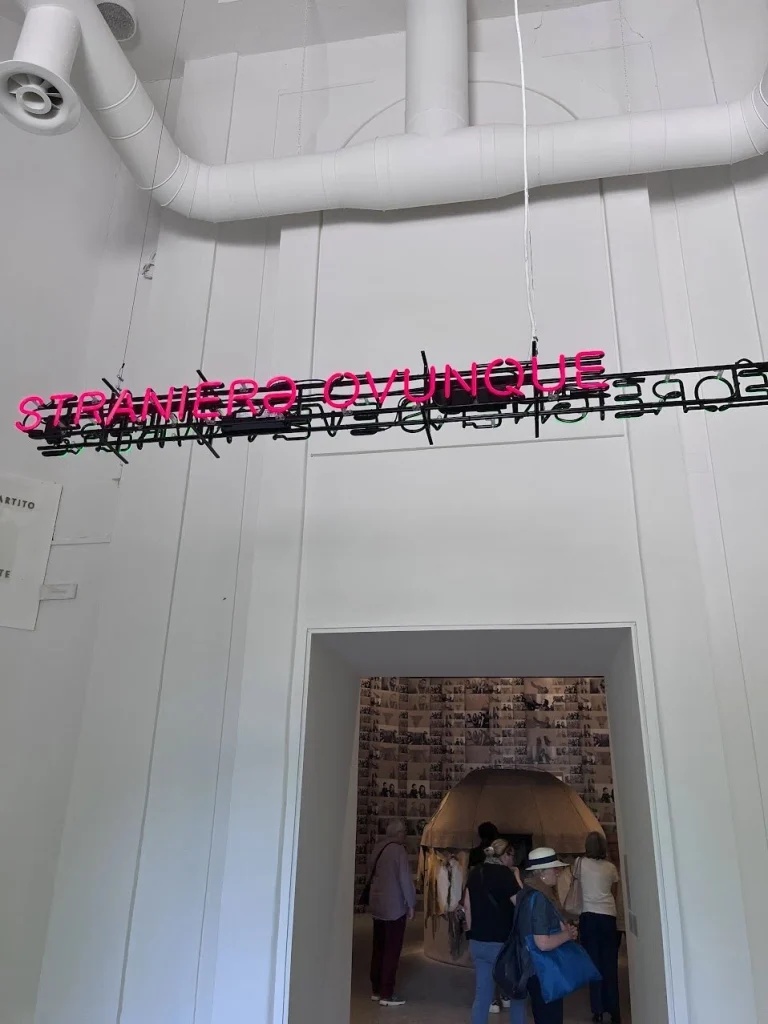

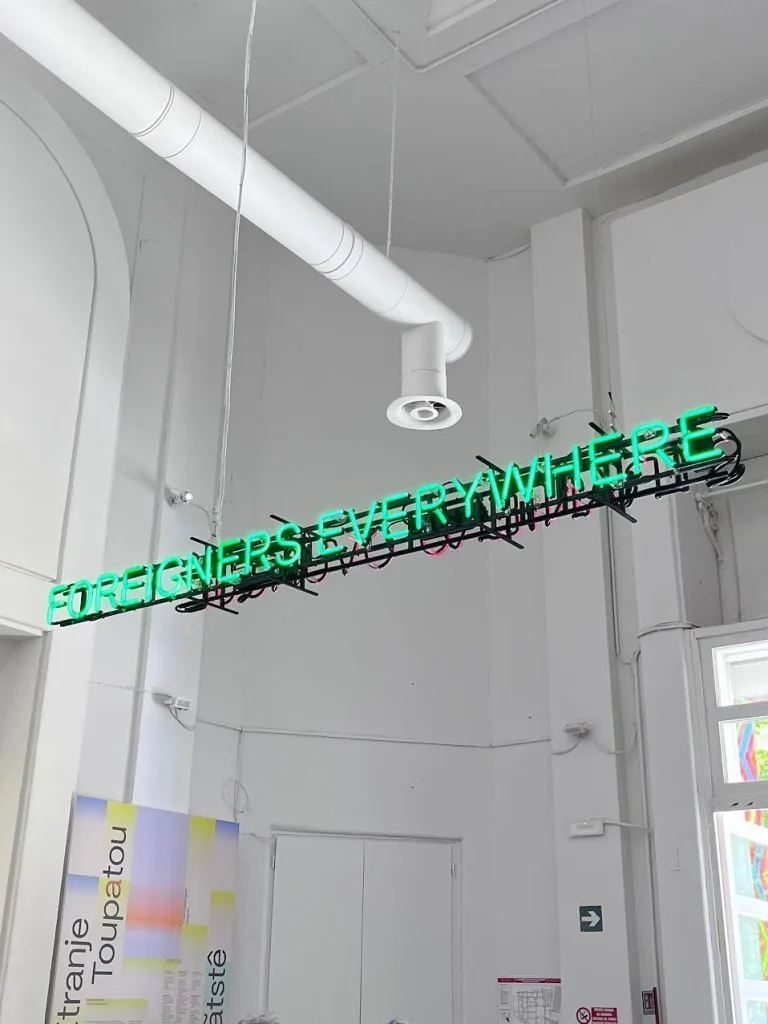

This year’s theme: “Stranieri Ovunque / Foreigners Everywhere”

According to Bijutsu Techo: “It derives from the name of a Turin collective that fought racism and xenophobia in Italy in the early 2000s.”

I viewed the exhibition with this Venice Biennale theme in mind. The German Pavilion evoked humans as outsiders, while at the French and Australian pavilions, I experienced a double sense of incomprehension—being a foreigner myself, viewing foreign exhibitions in a foreign country. There was also comfort in the absence of labeling here.

Regarding foreigners, I had experienced being treated as “invisible” as an Asian during my journey to Venice.

In business trips to German headquarters and America, I hadn’t noticed this much, but maybe that was because I had the company’s backing. At German headquarters, I noticed different attitudes between how colleagues treated Asian employees working there normally versus Asian or Eastern European people working in the canteen. (Maybe because colleagues were friends, but the gazes felt different.) In my 2022 America trip, colleagues went maskless, but people working cleaning jobs or in the canteen wore masks. I imagined they probably couldn’t afford to take sick days.

Foregrounding foreigners. Such things must be said. That must be the current moment.

Later, I saw this sign at Arsenale: “どこでも外国人” (Foreigners Everywhere)

I think I saw tweets saying this was incomplete Japanese, but let’s consider the English “FOREIGNERS EVERYWHERE.” I had always understood it as “foreigners who are everywhere,” but the word “are” isn’t included. To indicate “are,” it should be “foreigners are everywhere.” Machine translation would produce “どこでも外国人” (foreigners everywhere) rather than “どこにでもいる外国人” (foreigners who exist everywhere), which seems to be what was adopted, but I can’t believe there was no native check.

This might seem trivial, but there’s a possibility it was presented as an incomplete sentence intentionally. I immediately recalled the 2019 Okayama Art Summit “IF THE SNAKE”—a key phrase deliberately presented as an incomplete sentence.

Humans have a function to automatically complete information. While convenient, this creates troublesome misunderstandings and resulting resentments. I consider this a kind of bug, and I think art has a debugging function. This was precisely a moment of being debugged.

In Venice, a global tourist destination, I am a foreigner. The languages I hear include German, French, Italian, English, Chinese, and various others. For Venice locals, foreigners are indeed everywhere, visible anywhere. What about when I return to Japan? In current Japan, called overtourism, foreigners are everywhere.

Somehow uncomfortable, incomplete words make you think about the relationship between meaning and language, extending to cultural backgrounds. Culture and codes built up through accumulated daily life sometimes show exclusive aspects.

Italy, after 15 years, seemed to have increased not only tourists but also immigrants.

Arsenale: Mapping Journeys

I spent until about 3 PM at Giardini. For lunch, I drank Coca-Cola and headed to Arsenale.

Paintings, installations, and quite a lot of works are displayed, plus there are national pavilions. It’s a single path, so it’s easy to see, but if you engage with each work individually, it feels like no amount of time would be enough.

We were greeted by the Golden Lion winner Mataaho Collective’s work. Depending on timing, many people gather here too.

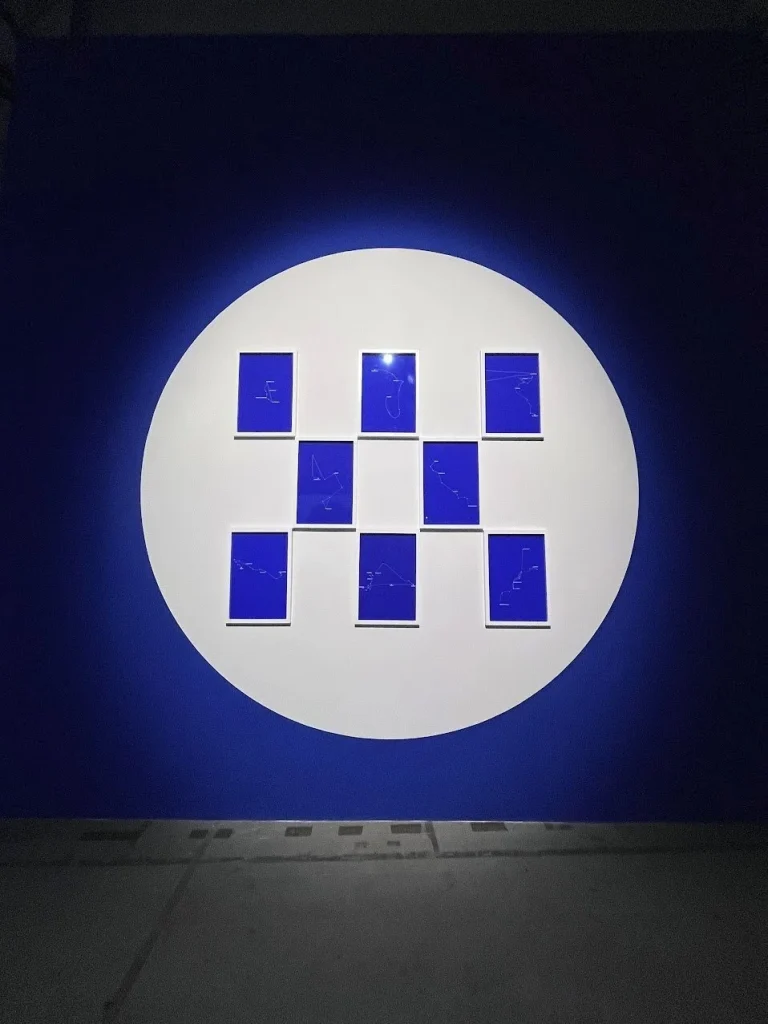

What left the strongest impression at Arsenale was “Mapping Journey.”

This work by Moroccan-French artist Bouchra Khalili features interviews with immigrants (including undocumented immigrants?) who came to Italy. The first I saw was an interview with someone who came to Italy from Bangladesh. They paid money to brokers, reached Eastern Europe but were caught and sent back. They went to Africa, aiming for Italy by boat from Libya or Tunisia.

Running out of money, getting arrested, shipwrecking and being rescued by Australian ships, thinking they could walk because land was connected but actually facing near-death experiences in high mountains—it was harrowing, but the interviewee calmly drew lines on a map as if recalling those times.

They came to Italy but hate Italy. They want documents. The ultimate goal is to reach Northern Europe. The audio of such interviews, represented by lines drawn on maps, evokes journeys that seem simple but were actually harrowing.

These lines drawn on maps were presented as drawings.

The shop where I stopped to buy requested souvenirs was run by someone from Bangladesh. Not a street stall but an actual store, selling typical Venice souvenirs. We communicated in English. He probably also speaks Italian. When I tried to pay, he said cash only—apparently a bank approval issue. What I had seen in Mapping Journey. That was (naturally) only part of it, and many foreigners had flowed in. When I told him I was from Japan, he seemed happy and spoke rapidly about himself.

Reflections on Global Art and Local Realities

I rushed through the Arsenale exhibition, so I returned on the second and third days. I thought I had seen everything at Giardini too, but there were unvisited rooms in the Central Pavilion. I wasn’t aiming to see everything, but rushing leads to oversights. I think it would be difficult to see everything in one day.

Pavilions scattered throughout the city can be viewed without tickets.

At the Kazakhstan Pavilion and Mongolia Pavilion, explanations were given by what appeared to be local students working part-time, but they provided perfect explanations. Volunteers explain at Japanese art festivals too, but they rarely manage explanations of this caliber—I was impressed.

What I noticed at various pavilions was that artists and curators were listed together. While this should be obvious, virtually every exhibition showed curators’ names alongside artists’ names with equal prominence.

Finally, at Arsenale, from the video work archive, Thunska’s “Damnatio Memoriae” caught my attention.

When I passed by, black and white footage of post-Hiroshima atomic bomb aftereffects research was showing—a burned boy’s face. Seeing that face, Hiroshima immediately came to mind, which I think was due to the aforementioned codes. Warning signs were posted about sensitive imagery, and appropriately so, as dissection footage was also presented. It concluded with pre-WWII Hiroshima footage before scene changes.

It stated that Teresa Teng eased Japan’s post-war isolation and opened pathways for exchange with Greater China. I found this an interesting perspective. She became popular in Taiwan, China, and Korea, serving as a bridge for diplomatic relations with each. And she opened pathways to Southeast Asia. The video played “Toki no Nagare ni Mi wo Makase” (Let Yourself Flow with Time).

The film continued further, but due to time constraints, I couldn’t watch it all. A Thai film director—I’d like to see more of their work another time.

For me, the Venice Biennale was not only an encounter with global art but also a process of recognizing how identities, languages, and histories interweave—reminding me that foreignness is everywhere, even within oneself.

Exhibition Details

60th Venice Biennale

“Stranieri Ovunque / Foreigners Everywhere”

April 20 – November 24, 2024

Venues: Giardini, Arsenale, and various locations throughout Venice

Note: This review reflects personal observations and experiences during a three-day visit to the 60th Venice Biennale. The complexity and scale of the exhibition means many significant works and experiences necessarily remain unmentioned.