“Asymmetrical Gazes,” a group exhibition held at aaploit in November 2025, brought together three artists in their twenties to interrogate the “asymmetry” of power latent in the gaze, each working through distinct media and perspectives. Asano Miyabi took as her point of departure the compositional structure of “the male who paints / the female who is painted,” a formula repeated throughout art history, and made visible its historical stratification.

In Venus and Tantō in a Landscape, a reclining, semi-nude woman extends three ten-thousand-yen notes toward a male figure with an infant’s body and an adult’s head. The man, in turn, reaches out as if to receive them. What first arises in this scene is an overlay of familiarity and dissonance. Asano references Palma il Vecchio’s Venus and Cupid in a Landscape, but the juxtaposition of classical style and contemporary visual language introduces a quiet tension into the picture plane.

Pastiche is imitation—it involves the borrowing and hybridization of styles. Yet whereas homage often carries the rhetoric of “respect,” the substance of pastiche remains ambiguous. Fredric Jameson, in particular, sharply pointed to the danger of imitation losing its critical edge and collapsing into empty repetition. This essay explores whether Asano’s practice remains within Jameson’s “blank pastiche” or whether it disrupts and repositions that structure.

The Same Model, Two Faces

Of the five works Asano presented in the exhibition, Venus and Tantō in a Landscape and Woman with Beautiful Eyes depict the same model—a sex worker. Yet her expressions differ between the two. In the former, she offers a soft gaze; in the latter, her expression is somewhat hardened.

This “repetition of the same model” evokes the practice of her reference, Palma il Vecchio. Palma painted what is believed to be the same woman in two different formats: as a mythological subject (Venus and Cupid in a Landscape) and as a portrait (La Bella). Art history has inferred her identity from features such as the dimple in her chin. And this woman was likely a high-class courtesan. The rhetoric of mythological subject matter functioned as a device to veil the reality of sexual and economic exchange.

Asano replaces this mythological rhetoric with “tantō“1 and ten-thousand-yen notes, thereby foregrounding the economic structure that had been concealed. In Palma’s painting, Cupid aimed an arrow at Venus; Asano reverses this directionality, creating a composition in which Venus extends money toward the “tantō.”

“Tantō” is industry jargon in host clubs, referring to the host assigned to a table. The nomenclature of host clubs—addressing female customers as “hime“2 (princess)—operates in parallel to the mythological appellations of the Renaissance (Venus, Flora). Both fictively transform economic exchange into romance.

What Asano exposes is the persistence of this structure. Just as mythological names legitimized sexual objectification, the term “hime” fictively converts an economic relationship into romance. Asano does not critique from outside art history; by adhering to the same style and the same compositional devices, she makes visible the concealed structure from within.

Asano reveals the economic reality that Palma had hidden within mythological rhetoric. Cupid’s arrow signifies mythological narrative. But the sign of the ten-thousand-yen note translates that mythology into economic exchange. Who is paying whom, and for what, emerges on the picture plane.

And then there is Woman with Beautiful Eyes. Here Asano further foregrounds what Palma had rendered invisible: the concept of “the working face.” Moreover, in Woman with Beautiful Eyes, the spring flower held in the right hand (a motif alluding to new growth and birth) is replaced with a condom.

The gentle face and the working face—this difference exposes the structure of emotional labor in sex work. Palma used the same model but rendered this dimension of labor invisible. Through the stylistic distinction between mythological subject and portrait, the model remained “goddess” and “beautiful woman.” But Asano, by repeating the same structure, represents “labor.” What Asano demonstrates is the fact that this structure has persisted while updating its styles.

What is crucial is that Asano executes this exposure in the same style as Palma. The same model, the same compositional contrast, the same stylistic language. She does not critique from outside art history. By using the same structure as art history, she makes visible from within what that structure has concealed.

Two Points of Entry for the Viewer

A question arises here. Does the critical effect of Asano’s work operate only for viewers who possess art-historical knowledge? If art-historical literacy is presupposed, the reach of the critique remains limited.

However, Asano’s practice has two points of entry.

Venus and Tantō in a Landscape moves from art history toward the contemporary. Viewers familiar with classical painting recognize, through the insertion of signs like “tantō” and ten-thousand-yen notes, the structure that the source had concealed. Here, art-historical knowledge functions as a trigger for critique.

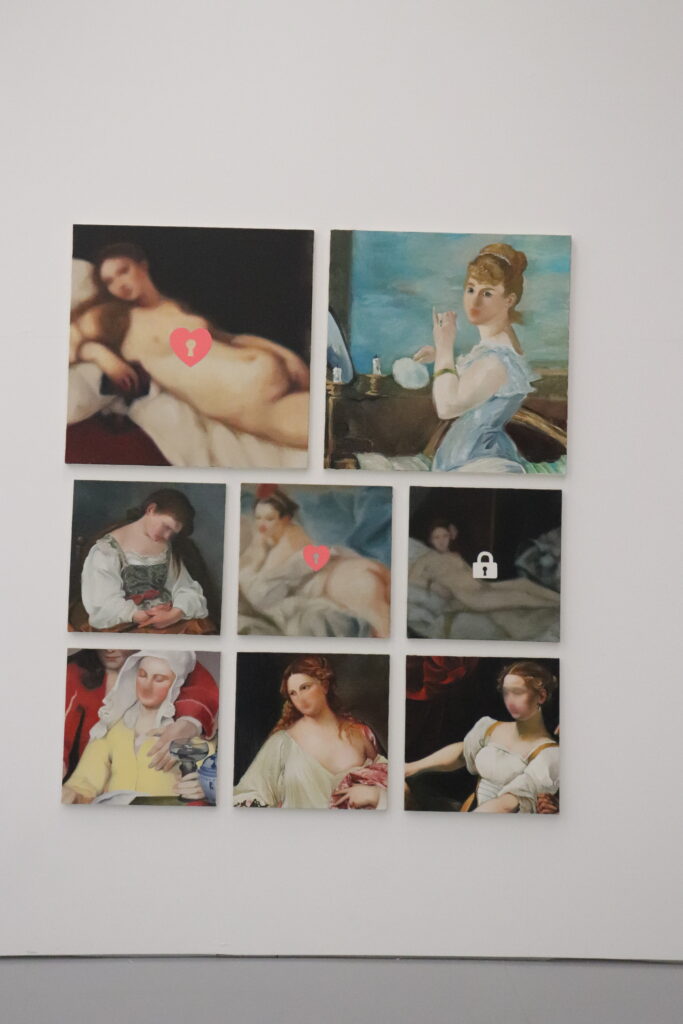

On the other hand, Asano’s other series—works that add mosaic censorship and heart-shaped lock icons to nude paintings by Titian and Caravaggio, the Shamenikki3 series—functions in the opposite direction. It employs the visual language of commercial sex-industry websites. These works are identifiable even for viewers unfamiliar with art history. Viewers are led to the discovery that “this masterpiece shares the same structure as images posted on sex-industry websites.” Here, contemporary visual literacy functions as a device that enables viewers to “rediscover” the structure of classical painting.

Asano’s practice opens in both directions. Viewers who know art history experience critique through reference from the classical to the contemporary. Viewers who know contemporary visual language experience critique through reverse illumination from the contemporary to the classical. Whichever entry point one takes, the destination is the same: the structure of visual consumption and economic exchange shared by art history and the contemporary sex industry.

This bidirectionality extends the reach of critique. Critique is no longer the exclusive privilege of those with art-historical education. Rather, viewers with different visual literacies are each guided from their respective entry points to the same structural exposure. Asano’s work functions as a device that presupposes differences in viewer knowledge while activating critique beyond those differences.

Jameson, Owens, and Asano

In the 1980s, Fredric Jameson diagnosed a situation in which imitation could no longer function as critique. For parody to operate, a shared norm is required—a collective agreement about what is “normal” and what constitutes deviation from it. But with what Lyotard called “the end of grand narratives,” that norm itself collapsed.

“So there remains somewhere behind all parody the feeling that there is a linguistic norm in contrast to which the styles of the great modernists can be mocked.” —Jameson

In a situation without norms, deviation can produce neither laughter nor criticism. What is being mocked, what is being problematized, becomes unclear. What emerges is what Jameson calls “blank pastiche.”

“That is the moment at which pastiche appears and parody has become impossible. Pastiche is, like parody, the imitation of a peculiar or unique style, the wearing of a stylistic mask, speech in a dead language: but it is a neutral practice of such mimicry, without parody’s ulterior motive, without the satirical impulse, without laughter, without that still latent feeling that there exists something normal compared with which what is being imitated is rather comic. Pastiche is blank parody, parody that has lost its sense of humour.” —Jameson

For Jameson, pastiche is the imitation of style that lacks the critical motive parody possessed. There is no satire, no laughter, no “normal” against which to contrast. Style is quoted, but meaning is not interrogated. History is referenced, but historicity is lost. Imitation devolves into neutral, empty repetition that says nothing.

Meanwhile, Craig Owens, working in the same period, discerned a different possibility within practices of quotation. For him, the allegorical method was an operation that adds new layers of meaning to existing images, thereby displacing their original meaning. Quotation is not mere reproduction; through the transposition of meaning, it can be converted into critique.

Yet Asano’s practice differs from both. Asano is not adding new meaning. Rather, she makes manifest—through the style itself—meanings already immanent in the source (meanings that had been concealed within art history’s stylistic rhetoric).

Does Asano’s stylistic adherence remain within Jameson’s “blank pastiche,” or does it disrupt that structure and open new possibilities? Taking this question as its axis, I attempt a repositioning of pastiche.

Asano adheres to style. The composition of classical painting, the smooth surfaces. But simultaneously, she substitutes signs. Cupid becomes “tantō“; the arrow becomes ten-thousand-yen notes. Stylistic adherence and semiotic inversion are executed simultaneously. Moreover, this “inversion” is in fact “exposure.” Asano makes manifest, through the style itself, structures that already existed in the source.

This is the response of “turning around” when asked “left or right?” In Asano Miyabi’s Venus and Tantō in a Landscape, we are looking at a beautiful classical painting. At the same time, we are looking at the exposure of economic and sexual structures that art history has concealed. It is not one or the other. Both are simultaneously established, maintaining their tension. The persistence of this paradox is the intensity of Asano’s practice.

Conclusion: Proposing the Concept of Critical Pastiche

Asano’s work disrupts the concept of “blank pastiche” as formulated by Jameson. Style is certainly imitated. But this imitation is not neutral repetition lacking sensitivity to history. Rather, it is refunctionalized as a means to make visible the structures that style has concealed.

I propose to call such practice “critical pastiche.” Critical pastiche is a form of imitation that fulfills the following conditions:

- Stylistic Adherence: Classical styles and historical visual codes are consciously adopted, executed not as external criticism but as internal operation.

- Structural Manifestation: Economic, sexual, and institutional structures already immanent in the source are made visible through the style itself. This is not the addition of meaning but the lifting of concealment.

- Layered Critique: Critique of the present and critique of the history that has reproduced these structures arise simultaneously. The form of imitation itself becomes a device that amplifies critique.

- Bidirectional Circuit: Viewers with art-historical education and viewers with contemporary visual literacy are both guided from different entry points to the same structural exposure.

Asano’s practice is the reactivation of critique through imitation, appearing after imitation had lost its critical capacity. Past styles are no longer merely objects of quotation. They are reactivated as media that expose the structures they themselves had concealed. Critical pastiche is a form of critique that appears after the death of imitation, and Asano Miyabi’s work is its exemplary practice.

Notes

References

Jameson, Fredric. “Postmodernism and Consumer Society.” The Cultural Turn: Selected Writings on the Postmodern, 1983–1998. London: Verso, 1998.

Lyotard, Jean-François. The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Translated by Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984.

Owens, Craig. “The Allegorical Impulse: Toward a Theory of Postmodernism.” October, vol. 12, Spring 1980, pp. 67–86; vol. 13, Summer 1980.

Footnotes

- Tantō (担当): A term used in Japanese host clubs to refer to a host who serves a particular female client. The word literally means “person in charge” or “representative.” ↩

- Hime (姫): Literally “princess.” In host clubs, female customers are addressed as hime, a rhetorical device that transforms economic exchange into the fiction of courtly romance. ↩

- Shamenikki (写メ日記): “Photo diary.” In the Japanese sex industry, workers post daily photos and updates on commercial websites to attract clients. These posts typically feature selfies with mosaic censorship over intimate areas and decorative elements like heart-shaped lock icons. ↩