A Review by Saito Tsutomu

Originally published in Japanese on note.com

Voice of Void by Ho Tzu Nyen examines how people engage with history under contemporary conditions of information and technology. Although the work refers to philosophical discussions from Japan during the wartime period, its main concern is not historical evaluation itself. Instead, it asks how thinking, mediated by systems and devices, can become separated from lived reality.

First shown in 2021, the work uses virtual reality not to create a fully immersive experience, but to expose the limits of immersion. The VR headset restricts vision, adds physical weight, and fixes the viewer’s position. Small movements of the body change the image, but the body itself remains unseen. This produces a situation where perception is active while physical presence feels reduced.

In this setting, viewers are placed in the role of observers. They are able to watch and to listen, but not to intervene. This position recalls the way people encounter information today: through screens, recordings, and second-hand accounts. Knowledge is received continuously, yet it often remains disconnected from responsibility or action.

Rather than presenting clear answers, Voice of Void draws attention to this gap. It suggests a structural similarity between historical forms of abstract thinking and contemporary digital experience. The work does not accuse its viewers directly, but raises a question: how different is our position from those we observe from a distance?

Reconsidering the Kyoto School: Contemporary Significance

What Ho Tzu Nyen’s exhibitions question—beginning with “Ryokan Aporia” presented at the 2019 Aichi Triennale—is not only the intellectuals from 80 years ago, but also our own ways of understanding today, surrounded by information yet becoming detached from reality.

Cultural Context: “Ryokan” refers to traditional Japanese inns. “Aporia” is a philosophical term meaning an irresolvable contradiction or puzzle. The title suggests a space where philosophical impasses are encountered.

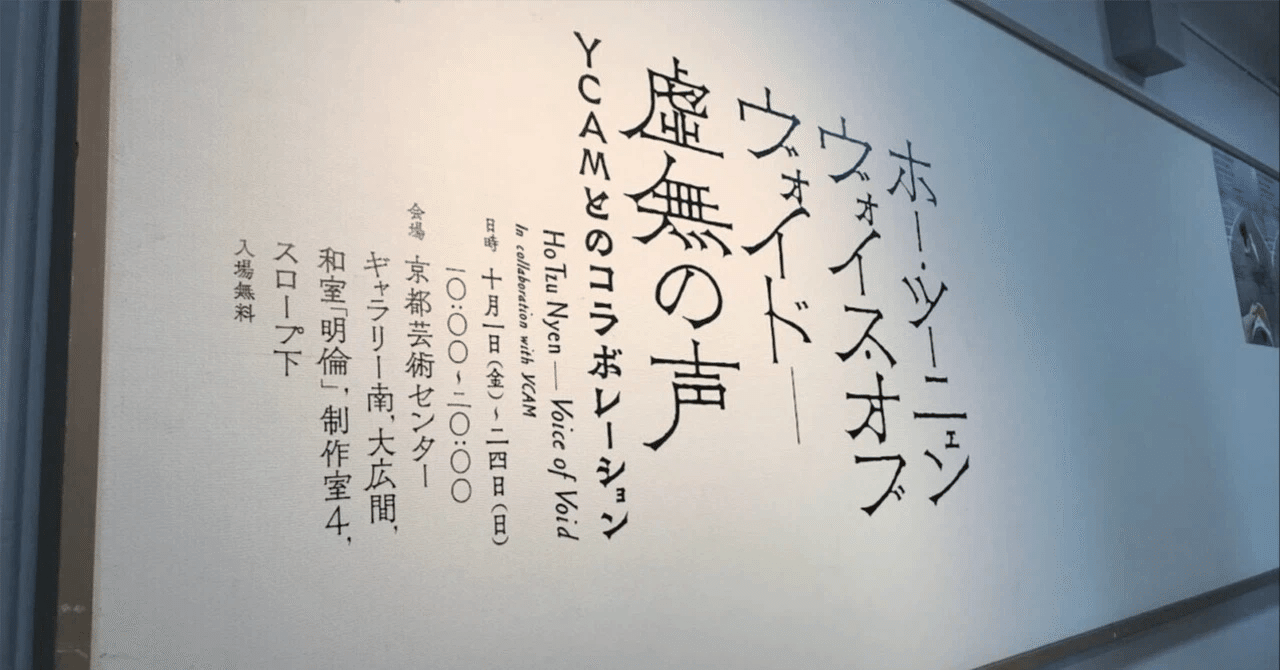

“Voice of Void” (first exhibited at YCAM in 2021) by Singapore-based artist Ho Tzu Nyen takes as its subject the thoughts and actions of Kyoto School philosophers during the Pacific War period, while examining the sense of “void” in contemporary digital society. The work functions not merely as historical critique, but as a device that brings into view the structural problems of contemporary society through its use of VR technology.

Cultural Context: The Kyoto School was a philosophical movement centered at Kyoto University in the early-to-mid 20th century, attempting to synthesize Western philosophy with Eastern thought. Its wartime role remains controversial, as some interpretations of its philosophy were used to justify Japanese militarism.

Structuring “Void” Through VR Technology

Virtual Reality as Paradoxical Critical Device

Ho Tzu Nyen’s use of VR technology represents an important case of technological critique in contemporary art. On the surface, it provides an “immersive experience” of history through cutting-edge technology. At the same time, it strategically uses the bodily constraints that come with VR—the weight of the headset and the restriction of the visual field.

As you stand, sit, lie down, or stay still while wearing the headset, your viewpoint changes. Through these changes in posture, what becomes visible is the gap between the experience happening inside the headset and the invisibility of your own body. Perception and physical sensation become separated.

Through the physical discomfort of the VR headset’s weight and the narrowness of the visual field, viewers experience a situation where only information flows in. This points to something familiar in contemporary society: how we encounter the world through smartphone and computer screens, becoming separated from the complexity of reality and the pain of others.

The gap can be understood this way:

- “Experience” in virtual reality ↔ “Understanding” through abstract thought

- Absence of physical pain ↔ Distance from battlefield reality

- Illusion of visual reality ↔ Illusion of understanding through philosophical concepts

The Dual Structure of “Voice of Void”

The work’s title carries two meanings across different time periods.

The first meaning is the hollow voice that emerges from the Kyoto School’s concept of “absolute nothingness” (zettai mu). It presents the historical fact that Nishida Kitarō’s philosophy of “absolute nothingness” functioned as abstract theory detached from reality, and its interpretation as lofty ideals became an “empty voice” that sent young people to their deaths.

Cultural Context: Nishida Kitarō (1870-1945) founded the Kyoto School of philosophy. His concept of “absolute nothingness” became controversial when some interpreters used it to philosophically justify Japan’s wartime actions, though Nishida’s own relationship to this appropriation remains debated.

The second meaning is the voice without substance that resonates in contemporary digital society. The flood of information lacking bodily presence—through social media, VR, games, and so on—appears as screen-mediated “knowledge” and “experience,” but often prevents genuine understanding and empathy. This shows a contemporary form of “void.”

The Kyoto School’s “Suspended” Situation and Contemporary Resonance

Spatial Expression Through Three-Layer Structure

The work has a vertical three-layer structure:

- Upper layer: The space of “ideals” flying through the sky in mobile suits (Tanabe Hajime’s philosophy of life and death)

- Middle layer: Scholars’ roundtable discussions in a ryōtei (traditional restaurant) and Zen meditation space

- Lower layer: The prison where Miki Kiyoshi and Tosaka Jun died

Cultural Context: Tanabe Hajime (1885-1962) was a key Kyoto School philosopher. Miki Kiyoshi (1897-1945) and Tosaka Jun (1900-1945) were Marxist philosophers who died in prison during wartime suppression of leftist intellectuals.

This structure expresses the Kyoto School’s complex position in spatial terms. They existed in a “suspended” situation. While they philosophically justified the war in deference to the army, they were simultaneously viewed as ideologically dangerous by the Special Higher Police (Tokkō) and became subjects of surveillance and suppression.

Cultural Context: The Special Higher Police (Tokkō) was Japan’s thought police during the militarist period, responsible for monitoring and suppressing “dangerous thoughts.”

The lofty ideals (upper layer) and tragic reality (lower layer) frame the intellectuals’ position (middle layer), which viewers experience literally as vertical movement. When you stay perfectly still, you enter a meditation space that feels detached from the everyday world. But the moment you move even slightly in surprise, the scene switches immediately and you wonder if what you saw was an illusion.

This ideological ambiguity and political instability resembles our contemporary situation remarkably. We think we’re cooperating with systems while being constantly monitored. We act with good intentions but find ourselves caught in structural problems. The “suspended” position of intellectuals from 80 years ago overlaps with our own condition today.

“Sand of Asia” and the Forced Participation of Bystanders

An important reference point for the work is Ōya Masuzō’s Sand of Asia. The position of the journalist as battlefield bystander—forced participation through “writing it down” and the compulsion to silence—forms the structural foundation of the VR experience.

Cultural Context: Ōya Masuzō (1900-1970) was a journalist whose 1942 book documented the Japanese military campaign in Southeast Asia. His reflections on the journalist’s complicit position—required to record but forbidden to protest—raised questions about intellectual responsibility during wartime.

Viewers are positioned as “stenographers” of the roundtable discussion, required to record the testimony of history but given no right to speak. This forced participation as witness-recorder is similar to the structure of contemporary information consumption. We record and share events through social media and other platforms every day, but we lack the power to create structural change.

As a structure of paradoxical dépaysement, viewers can interrupt the experience at any time, yet once they know the facts, they find themselves in a situation where it is difficult to escape ethically. This “freedom to leave / freedom to stay” creates the weight of choice and responsibility, raising fundamental questions about how we engage with information in contemporary society.

Note: “Paradoxical dépaysement” refers to being made to feel strange or disoriented in a familiar context—a term explored in other aaploit critical writings.

Decolonial Perspective and Critique of Regional Concepts

The Political Nature of the Term “Southeast Asia”

Ho Tzu Nyen’s origins in the Malay Peninsula bring a decisive perspective to the work. His observation that the Kyoto School completely lacked any viewpoint toward Asian countries when discussing the “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” carries the weight of someone directly affected.

Cultural Context: The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere was Japan’s wartime propaganda concept claiming to liberate Asia from Western colonialism while actually establishing Japanese imperial control.

What is important is that Ho Tzu Nyen himself clearly points out the political nature of the term “Southeast Asia.” This regional concept was created by Japan during World War II. As a Japan-centered directional expression for regions where historically no unified state had existed, it embodies the ideological framework of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

Animation and Cultural Memory

What is particularly notable is that the work represents war through animation (mobile suits), a cultural product of contemporary Japan. The significance of Ho Tzu Nyen’s use of robot animation appropriating Gundam’s “Zaku” takes on meaning as a kind of spiritual practice that revives the voices of the dead, considering that the etymology of “animation” lies in “animism.”

Cultural Context: The Zaku is an iconic enemy mobile suit from “Mobile Suit Gundam” (1979), whose design was influenced by World War II Japanese military aesthetics, particularly the Zero fighter plane. The visual language of mecha anime has long carried complex associations with Japan’s military history.

Furthermore, this expression can be read not as mere critique, but as a renewal of historical consciousness that critically uses the very history of how postwar Japanese anime culture has depicted war as “cool.” Just as the Zaku inherits the memory of the Zero fighter, it asks viewers how popular culture has processed and transformed the memory of war.

Exposing Structural Similarities: 80 Years Ago and Now

What the work exposes is the similarity in ways of understanding between intellectuals from 80 years ago and people today. This becomes visible through comparing the Kyoto School (1940s) with contemporary digital society (2020s):

- Armchair theorizing / Online discussions

- Reality-escaping speculation / Escape into virtual spaces

- Physical isolation from battlefields / Screen-mediated war reporting

- Lack of imagination for others’ pain / Online dehumanization of others

- Intoxication with abstract ideals / Sensory numbness from information overload and loss of “sense of reality”

- Deference to the army and surveillance by Tokkō / Cooperation with systems and coexistence with constant surveillance

Signs of “Void” in Contemporary Digital Society

- Gamified war experience: Entertainment of “combat” without the weight of pain or death

- Sensory numbness from information overload: The danger of “feeling like you know” through mass information

- Escape into virtual space: The tendency to look away from the complexity of reality

The insight that intellectuals from 80 years ago and people today exist in the same “void” is at the core of the work.

Collaborative Production Model in Contemporary Media Art

Transparency in Specialized Division of Labor

This work also draws attention to a new approach: making the production process visible. In “Ryokan Aporia,” the email that the curator sent to Ho with interview materials from the proprietress of Kirakutei was presented as part of the work. It presents the collaborative process—which tends to be concealed in traditional art production—as part of the work itself.

The realization of this work required essential collaboration across multiple specialized fields:

- Ho Tzu Nyen: Oversaw the overall concept and formulation of the “questions”

- Nose Yōko: Handled materials collection and translation

- YCAM: Technical supervision and system development

- Speed Inc.: Produced high-quality CG animation materials

This kind of specialized division of labor represents a production method that moves beyond the era when artists had to master every technical skill themselves. By bringing together specialists with the highest level of skills and knowledge from each field, it achieves depth of expression and technical completion that would be impossible for any individual.

Pierre Huyghe employs multiple researchers for his work production (exhibition making). For “Sototama Shii” permanently installed at Dazaifu Tenmangu, he created an environment where bees build nests in Tobari Kogan’s sculpture. This could not be realized without cooperation from various specialists.

Generation of “Questions” by the Artist

The essential value of contemporary art works lies in posing fundamental questions to viewers. Ho Tzu Nyen integrates the vast materials collected and translated by Nose Yōko with the technical contributions of each specialized institution, raising fundamental questions such as “What makes you different from the Kyoto School philosophers?” and “What is the ‘void’ in contemporary information society?”

This is the artist’s essential function. Not to provide answers, but to create a device that prompts thinking, transforming audiences from passive consumers into active thinkers. The intellectual curiosity that makes you want to seek related materials after viewing comes precisely from this power to generate “questions.”

The Importance of Physicality and Material Experience

In the 2022 winter re-staging of “Ryokan Aporia,” viewers physically experienced the freezing cold of the late-Meiji period wooden building. They gained the experience of sitting on zabuton cushions and looking up at the footage from Ozu Yasujirō’s low camera angle. This bodily experience provides a sense of reality that cannot be achieved in VR, strengthening the work’s critical effect.

Cultural Context: Ozu Yasujirō (1903-1963) was one of Japan’s most influential filmmakers, famous for his distinctive low-angle camera position approximating the viewpoint of someone sitting in traditional seiza posture on tatami.

Devices that appeal to physical senses—such as acoustic effects through whispered voices and light staging through transparent screens—give the work a persuasive power that cannot be achieved through digital technology alone. Viewers understand the weight of history not just by knowing information, but by physically feeling it.

The use of a historical location (Kirakutei) combined with contemporary expression techniques means that the building’s history—from sericulture industry to military-related use to postwar automotive industry—supports the work’s layered meanings.

Generation of Fundamental Questions as Media Art

Ho Tzu Nyen’s series of works demonstrates new possibilities for historical representation in contemporary media art. Through the combination of the affected-party perspective of an artist from the Malay Peninsula, meticulous materials collection and translation by Japanese researchers, advanced system development by technical institutions, and video production at specialized studios, they generate a distinctive effect that neither conventional academic research nor art works alone could achieve.

What the work ultimately generates is a fundamental question of how to receive history as a problem in the present tense. Before criticizing the Kyoto School philosophers, viewers are asked to confront the fact that they themselves exist within the same cognitive structure. This device for generating questions functions as constructive critique toward contemporary society, going beyond simple condemnation of the past.

What is particularly important is that Ho Tzu Nyen presents the reception of postwar Japanese anime in Asian countries as fact rather than condemning it. This stance embodies the essence of media art. It questions the power and influence that media itself possesses, makes visible the complexity and ambiguity of cultural influence, and leaves judgment to viewers themselves. The way Japanese popular culture has functioned and been received across borders presents media’s essential mechanisms in artistic form.

Through the integration of all these elements—the maturation of production methods in contemporary media art, the transparency of commissioned production processes, the creative combination of technology and historical research, and the effective contrast between bodily experience and virtual reality—”Voice of Void” opens new horizons for historical consciousness and contemporary critique. At the same time, as a fundamental questioning of media’s own functions and influence, it demonstrates the possibilities of media art in the truest sense.

About the Reviewer

Saito Tsutomu is a Tokyo-based art critic and gallery director. His writing focuses on contemporary art practices that engage with history, media, and systems of knowledge.

With a background in technology and business consulting, and an MFA from Kyoto University of the Arts, Saito approaches art criticism from an interdisciplinary perspective that bridges theoretical inquiry and practical experience. His research has included sustained engagement with the work of Pierre Huyghe.

Through his writing and curatorial practice at aaploit, he examines how contemporary art functions as a device for generating questions rather than providing answers.